How to Manage Non-Adherent Patients

Published on:

Patients who are non-adherent (formerly referred to as “difficult” or “non-compliant”) with their physician’s recommendations or medical advice risk injury to themselves and pose a liability threat for their physician. Non-adherent patients typically are those who do not follow post-treatment instructions; don’t keep appointments; don’t report information about worsening symptoms; fail to follow through on referrals to a specialist; don’t get recommended diagnostic tests; or don’t take their medications properly.

Reasons for non-adherence

Non-adherence is not always a deliberate act. Among the reasons some patients may not follow the doctor’s advice:

- They didn’t understand instructions;

- They forgot the doctor’s oral advice or don’t agree with it;

- They didn’t appreciate the seriousness of a medical condition;

- They were unaware of the urgency of a recommended follow-up visit, test or referral to another physician;

- They were confused by oral instructions for medication use;

- They could not understand the instruction due to a language barrier, hearing impairment, fear, mental confusion or low health literacy;

- They received conflicting advice from multiple treating physicians; and/or,

- They didn’t have insurance for medication, or coverage for diagnostic tests, surgery or additional office visits.

Physician’s role in non-adherence

A physician’s words, actions, inattention or silence can contribute to a patient’s non-compliant behavior. For example, when a patient is advised during an initial office visit to stop smoking or alter eating habits, but the subject is not mentioned again, a patient may conclude that the doctor no longer considers the advice significant. “He knows I still smoke, but he hasn’t mentioned it for two years, so he must not consider it much of a problem.”

Physicians can contribute to a patient’s failure or refusal to comply with medical advice in other ways. If their doctor spends too little time to explain the significance of a medical finding, recommended treatment, alternatives, and the expected outcome of treatment, patients may infer that these are not important issues. Some doctors impart most of their medical advice orally to patients, sometimes in language that is too technical for the average patient to absorb. Physicians can discourage patients from asking questions by showing impatience, belittling patient complaints, or by offering unrealistic advice. Telling an obese patient to “cut back on your calories” might be sound advice but could be impractical unless the patient is told how to reduce calories. Similarly, it may be a futile exercise to advise patients to “stop smoking” or to “drink less,” without considering the patient-specific factors that prevent their immediate compliance.

Non-adherence and litigation

Litigation experience demonstrates that non-adherent patients are liability risks. These patients may pursue a claim if they believe and can prove their noncompliance resulted from a physician’s unclear, inadequate or omitted advice. For example, a patient who suffers a serious medication side effect and fails to seek treatment may claim he was not informed of the side effect or that it could be related to the medication. Similarly, a patient who is injured due to vigorous activity following a surgery may claim the physician was negligent by telling him to “take it easy,” rather than giving more specific advice, such as “don’t raise your arms above your shoulders for at least 3 days” or “Do not be weight bearing for 7 days.” Employers of patients (or the patients themselves) who are released to work with instructions limiting them to “light duty” may not interpret the instruction in the same way as the physician intended for the patient comply with the instruction.

Litigation experience also demonstrates that patients who are willfully non-adherent have not shared their doctor’s advice or warnings with family members. Thus, when a patient’s noncompliance results in his or her death, survivors may blame the physician for failing to give the patient clear instructions. MIEC has settled a number of costly claims and lawsuits because doctors failed to document advice they gave to patients who in turn were non-compliant and caused or contributed to their own injury or death.

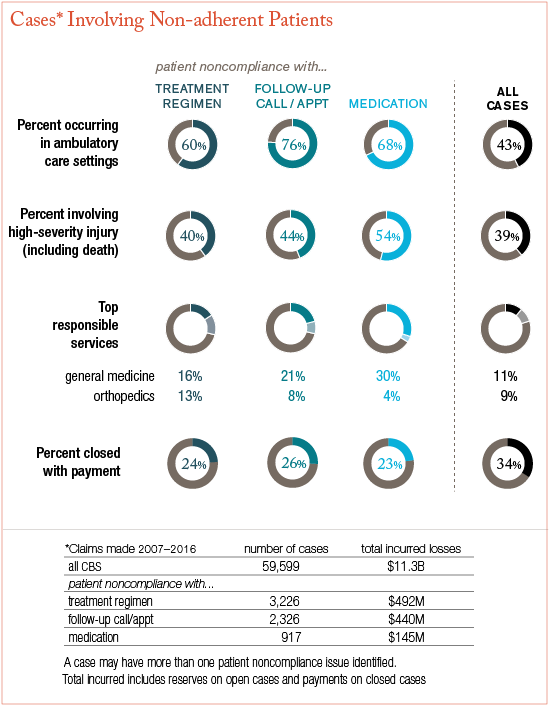

[SIDEBAR – Figure 1]

Figure I: “Malpractice Cases Involving Non-Adherent Patients,” CRICO Strategies in Patient Safety by Jock Hoffman, dated March 2018. Data from CRICO’s national Comparative Benchmarking System (CBS); all CBS cases asserted between 2007-2016.

Charting protects the doctor

After they have sustained an injury or an exacerbation of a medical condition, some non-adherent patients are quick to fault the doctor, or anyone but themselves.

Documenting a patient’s failure to adhere is an effective way for doctors to protect themselves from liability. A sufficiently detailed and timely progress note ordinarily affords protection. In cases in which the doctor had multiple conversations about the effects of a patient’s noncompliance, a note that includes details of exam findings, discussion and recommendations is beneficial.

In addition to timely documentation, these additional steps shield physicians from malpractice claims by non-adherent patients or their survivors:

Give clear instructions. Patients often need written information to help them understand a medical problem, its treatment and sequelae. Newly-diagnosed conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperthyroidism and cancer, to cite a few, entail many aspects a patient may not appreciate after only an initial oral explanation. Physicians are encouraged to supplement oral explanations, instructions, and recommendations with written information. This allows patients and their families to re-read and re-review details of their newly diagnosed condition as often as they need. Dispense written information for medications rather than relying upon package inserts or pharmacist review with your patents. Specify the name of the drug, what it is for, how it should be taken, significant side effects that should be reported to the doctor, precautions while taking the drug and what the patient should do if he or she misses a dose.

Schedule appointments practically. Allocate appointment slots according to patients’ needs. For more efficient scheduling, some practices schedule elderly patients at the end of the day, so that if more time is needed with them, the rest of the schedule is not delayed. Some practices set aside blocks of time before 8:30am and after 5:00pm to accommodate patients, whose work schedule makes midday appointments difficult. Patients who may have to take off from work without pay to see the doctor are more likely to go to the emergency department or an urgent care center for routine care their own physician could have provided. Many practices keep open two free time slots each day to accommodate urgent drop-ins or make up for unexpectedly long appointments.

Stress the degree of urgency. Explain to patients why they need to obtain a diagnostic test, see a specialist, or to follow specific medical advice; stress the urgency for the follow-up care. Document what you advised and the fact that you stressed the urgency. Patients can prevail in malpractice litigation if they prove that although the doctor gave appropriate advice, he or she did not mention the potentially serious effects of the delay and/or did not stress the importance of further treatment or diagnostic testing.

Obtain an informed refusal. Patients have the right to decline a physician’s advice for tests or treatment. The doctor is best protected if he or she documents that patients were informed of the consequences of their decision to refuse recommendations for treatment, medication, tests or referral. Document the discussion, specifically, the patient’s refusal to comply the recommendation.

Be a good listener. The amount of time physicians can practically spend with patients seems to diminish every year. Because the doctor’s responsibility to obtain information and act upon it remains the same, regardless of time pressures, physicians must make the best use of their time and listen well to what the patient says. Patients, too, are mindful that a doctor’s time is limited, and they may not want to cause friction by asking too many questions or taking too much of the doctor’s time. Patients can sense when a doctor is in a hurry or is impatient with them. Physicians are encouraged to avoid body language that signals impatience or inattention. Communication experts advise that good listening skills include: sit near or across from the patient rather than standing or hovering in a doorway; maintain appropriate eye contact; and avoid interrupting the patient who is trying to explain what he or she is experiencing.

Encourage questions. Many patients are reluctant to “bother” the doctor with questions and need “permission” to telephone the office if something troubles them. Others won’t volunteer information. “If my doctor thought it was important, she would have asked about it,” these patients typically contend. Physicians who ask, “Is there anything else you’d like to tell me” and who encourage their patients to speak freely, learn more than colleagues who assume that a patient’s silence is evidence that all is well.

Document failed appointments. Ask your staff to note failed appointments in patients’ charts. Most electronic medical record systems track missed appointments. Use a reminder system to contact selected patients whose missed appointments put them at risk. Often, what appears to be noncompliance is a simple oversight.

When all else fails… Accommodating patients who habitually fail to follow advice may seem admirable, but ironically such acquiescent behavior has been used against physicians who are sued by the patient or the patient’s family. In some cases, when doctors continue to provide treatment that is not effective or is not the treatment other physicians would have chosen because of the patient’s noncompliance, the argument is made that the patient was non-compliant with the doctor’s knowledge and permission. When reasonable efforts fail to convince the non-adherent patient to keep appointments, follow advice, take medications, or see a referral physician, after a final warning the prudent course of action may be to consider discharging these patients from the practice. The threat of losing their doctor may encourage some patients to be more compliant with the doctor’s advice.

Further Reading:

MIEC’s Managing Your Practice Advisory #2, “How to discharge a patient from your practice,” offers advice and includes samples of discharge letters.